All right the title is jokey, the thing is the Reformed tradition has subordinate standards. Now don’t go looking in the Westminster Confession, or Belgic or the Statement of Nature, Faith and Order of the United Reformed Church for statements about Subordinate Standards, you won’t find any. The simple reason is this is self referential these are the subordinate standards. That means for all URCs that the principle Subordinate Standard for us is the Statement of Nature, Faith and Order of the United Reformed Church. So saying we don’t have standards is a bit stupid!

There is one thing every one should spot I have so far and will continue to do so, use the term Subordinate Standards. They are Subordinate to scripture. The Protestant shout of “Sola Scriptura” means that practically they never ever have been the final statement on the faith. Doctrine can and is Reformed in order to bring it better in line with Scripture. This is alive and kicking in Reformed Churches. I can remember being asked how a hymn of Kathy Galloways could get into Church of Scotland hymn book where it would struggle with its feminist images into an Anglican one. The answer was simple, the images Kathy used were Biblical, therefore the question was not “Are these images feminist?” but “Are these images Biblical?” and if they are then they trump all questions about whether things were feminist or not. Many Subordinate Statements say exactly that.

Secondly Subordinate Standards are about where the faith has been. Have a look at Reformed Presbytery of North America’s list and really go down them. You will find an odd bunch of documents. There are the standards such as: the Apostles Creed and the Westminster Confession, but then look what else is there like: Metrical Psalms and the Acts of General Assembly of the Church of Scotland betweeh specific dates! This does not look to me like a group trying to specify Doctrine it looks far more like a list of documents they tell where the group has come from. To ask who we are is nearly always to ask who we have been.

The picture I tend to come back to is of cairns, they normally come from places where the originating group for some reasons feels that it is a good idea to make a statement about how they see the faith. The reasons can be various; I am almost certain that the Congregationalists insisted on one when the URC was formed. They did not want any pesky Unitarians getting their hands on any property of the new united church and therefore having a statement was essential (the Unitarians won’t have a statement because that might meanthose troublesome Congregationalist getting their hands on the property). I think it is instructive that the requirement in the United Church of Canada to become a member is that you assent to belief in the Trinity (not the incarnation or ressurection) and this was insisted on by Congregationalists. The memories of fights in church history die hard. However it has to be said that fresh statements at the creation of a merged denomination are common. They equally occur at times of crisis, points of turmoil and not always theological, quite a few of them are political. However most of the time we plod along with those we have got and don’t pay much heed to getting new ones.

|

| URC approach to “Substantial Agreement” |

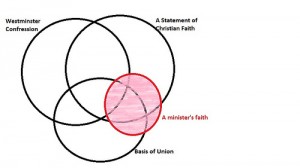

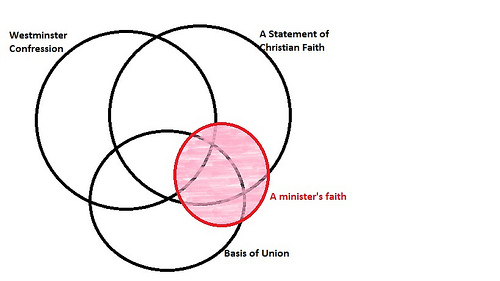

A while ago I drew two pictures of what we would mean if we required a ministers faith to be in substantial agreement with the subordinate standards. I suggested the URC’s approach was like the diagram shown here. I would suspect quite a overlap with the Basis of Union, maybe with quite a bit of agnosticism about parts of it, with other bits being inconcurrence with other Subordinate Standards which we accept. In other words the tradition is defined by having a broad scope with many overlapping subordinate standards and the requirement is that the faith falls mainly within those parameters. It does not mean that all ministers sign up to the same things exactly. Indeed although I have shown three here, there are at least another six named subordinate standards. I defy anyone to know them well enough that they can recall them at an instance and say what they agree and disagree with them let alone accept them all. Then there are the ones we don’t name but are included as “of the tradition” e.g. the Scots Confession. However what status is John Robinsons address to the Pilgrim Fathers at Plymouth. You won’t find it on the internet, I might put it up at some stage if I get hold of it, but the paraphrase in the form of We limit not the Truth of God (ignore the tune) is widely sung in the URC and I have heard quoted in theological debate. There is thus a deliberate ambiguity.

Yes I use the subordinate standards, they have been an important vehicle of my initiation into Reformed Theology, but I do not use them in a sort of lets try to believe twenty impossible things before breakfast style. I usually read them through quite quickly the first time, to try to get a feel of them, what is important and how they stand. Then and this is an ongoing process I turn to bits I see as significant and try and work out why. It maybe I disagree with them, in which case I need to work out why, or it might be a phrase gives me cause for reflection, time to look deeper at other understandings. So Subordinate standards are there to say where we have been, not to determine who we are. Remember “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” (George Sanayana) so we need methods of remembering where we have been and knowing why we have travelled to where we are.

This is going to depend on what you think the term “subordinate standard” means. If by it you merely mean that a denomination has to have some statement that declares what it requires one to believe then it is uncontroversial (not only within the Reformed tradition but in the Church catholic). In the case of the URC it is Schedule D of the Basis of Union and I doubt whether any mainstream Christian would find anything problematic in it (even the stuff about the civil authority).

If however you mean the distinctively Reformed Confessional subscription I think you’re wrong. The Congregationalist ‘A Declaration of Faith’ is very explicitly descriptive not prescriptive. It says it is not intended to tell anyone what they should believe nor is it intended as a disciplinary instrument (both primary purposes of a Reformed Confession – hence the practice of adding catechisms to them). It describes itself as a declaration rather than a statement because it says it is intended merely t report what Congregationalists already believe.

You are thinking in binaries a very dangerous thing to do in the Reformed tradition, it is never that simple. Subordinate Standards are neither Prescriptive nor Descriptive they are dialetical, that with which you must interact if you are to be considered working in the Reformed tradition. The tools for learning and understanding the Tradition. Notice I have not used words of agreement.

Have you looked at Reformed Presbytery of North America’s list. It is remember conservative with respect to the tradition. Can you tell me how the metrical psalms can be either prescriptive or descriptive of belief?

The Congregational Statement may describe what they already believe (although if you believe that you are naive, you put a group of doctors of the church in a room and tell them to agree a statement, several strong debates follow and the wording is the compromise that they have come to, it is therefore normally slightly further on than where the denomination is in the direction the doctors of the Church think the denomination should be heading), but is designed also to be used to teach what Congregationalist believe, to be used in negotiation with other traditions and to make claims about the nature of Congregational belief. In other words it often marks a change in discourse.

Also most Reformed statements are very careful to be clear about their lineage to historical confessions. Its our version of Apostolic succession, we need to show that our teaching is in line with historical understandings of the Church.

There is a view that having no subordinate standards means tolerant, this is nonsense. The Unitarians have no subordinate standards, but I would not have dared suggest that they were more tolerant than the Congregational church I grew up in. It was formed by the expelled Trinitarians from the central Presbyterian church when that went Unitarian. During my fathers time working at the Northern college only one member of staff in the Northern Federation was sacked for their theological views. The principle of the Unitarian college because he was a Buddhist Unitarian rather than a Christian one. The aim to define who is in and who is out is not dependent on having subordinate standards, it is a basic human desire.

If you think I am taking a personal line here, I suggest you start talking with older ministers in the denomination out side of Scotland. The Exploring Reformed Spiritualities had a group of them and when I mentioned Subordinate Standards as prescriptive they were incredulous. It is not what they believe. If you want you can take from Migiliore “Always subordinate to Scripture, the church’s common creeds and contemporary confessions provide hermenutical keys to what is central in Scripture and give succinct summaries of the mighty acts of God.” You are getting closer.

This is of course a matter of terminology. I resist the term “subordinate standards” because of its history. What it has meant has been a standard used as a disciplinary instrument. It has a quite specific lineage within Presbyterianism (which is where it originates) and to me brings the shadow of the heresy trial with it. This term was not part of the Congregationalist tradition and indeed comes from a way of thinking about church order and its relationship with doctrine quite contrary to that tradition (for good or ill).

On these differences between Congregationalism and Presbyterianism I’ve just read Romilly Micklem’s excellent PhD thesis. He demonstrates pretty conclusively, in my view, the differences between the two and the much more sceptical approach to tradition and to doctrine on the Congregationalist side (for good or ill, something he and I would not quite agree on).

No it isn’t its a matter of history, particularly the difference between English Non-Conformist and Scottish Church history.

You only see those with standards as persecutors, English Congregationalism understand that those without standards can equally be persecutors because that is our experience.

My question would be as an English of Congregational heritage, “if you don’t want standards why aren’t you Unitarian?”

Let me explain. Unitarians aren’t all Unitarian doctrinally, I know of at least two full blown Trinitarian ministers within the denomination. Their full title used to be “Unitarian and Liberal Christian Church”. The “Liberal Christian” is important, it is the strand that came out of English Dissent. “Unitarian” is from the Church of England. Liberal Christians were those who did not want to have standards. This is why Unitarians are calles “Non Subscribing Presbyterians” in Ireland. The important thing to realise is they also were the powerful within those congregations/denomination and drove out those who wanted standards.

Many of those who were driven out by these Liberal Christian Congregations formed new ones that took refuge in the Congregational Union. So no English Congregationalist believes that Subordinate Standards are essential to persecute, we have seen the opposite indeed it is our most recent experience of persecution.

I would suggest that your being caught up with the Subordinate Standards as the cause of persecution is hiding the real cause of persecution that are fear and power.

I really don’t understand why you want to insist on the phrase “subordinate standard”. Why is it (the phrase) important? I agree that orthodoxy is important and am glad that we have a statement of faith in the Basis of Union and that this statement is a clear affirmation of the catholic faith.

However the Congregationalists in England could never have had “subordinate standards” since they were opposed to the idea of a central authority to enforce it. A standard requires enforcement or at least measurement or it isn’t a standard.

That’s why the 1967 Declaration goes out of its way in its opening section to insist that it isn’t a prescription but a description, intended to tell people what Congregationalists actually believe rather than to tell Congregationalists what they should believe.

If you think this is a bizarre Scottish mis-reading of English history I suggest you ask Romilly for a copy of his thesis (he was very forthcoming when I asked him) and get a thoroughly English take on this history (which he’s researched much more thoroughly than I have).

First answer because it is the terminology recognised by other united church partners such as the United Church of Canada, and it is not there prescriptive either. Therefore it has ecumenical acceptance within the tradition that I will need persuading as requiring other terminology. I know of no better (and I do know of worse, although you can argue it is not good), terminology that is used ecumenically within the tradition

Secondly English dissenting practice is worse. Many congregations had covenants and members were expected to sign it before coming into Membership. These covenants were basically subordinate standards by another name, yes they borrowed from each other and could be very prescriptive over them. Congregationalists were not renowned for their toleration. This is not a case of Presbyterians bad persecutors, English Congregationalists nice tolerant Christians who were only persecuted (if you believe that go and talk to the Quakers, they will soon put you right). The best that can be said is that since the Restoration we have lacked opportunity and Oliver Cromwell and Henry Vane were pretty remarkable men for their age.

Thirdly the oldest Reformed Subordinate Standards were clearly written by people who knew their limitation and that they could not be applied prescriptively. The prescription is a later accreditation. Reformed theology is always contextual and always has been, it is always multi-voiced and English dissent is one of the most complicated voices there are. The dialectical use of them was always intended but that is more than descriptive while not being prescriptive. The change is quite interesting, it appears to be connected with the rise of Puritanism in England with its spill over to Holland and Scotland. This made faith centre the individual, rather than the community; “I believe” instead of “We believe”. It also has a lot of connection with nationalism both in Holland and Scotland. The synod of Dort’s real question was what is it to be a good Dutch man.

Fourthly I suspect if we do allow blame for what I see as caused by power and fear to rest on them, we will end up changing what is easy to no avail. To change the way we interact with power and fear is the work of the Gospel and a conversion of the will. Cheaper solutions don’t work and I’d rather people did not invest in them. The wish to rule others out so as to be sure you are in, is a wrong headed one, but having subordinate standards will not make one bit of difference to whether that happens or not. However reading them with intelligence will stop the daftness such as those reading “marriage is between one man and one woman” putting the emphasis on the sex of the participants rather than on the word “one” while I am very sure the originators did it the other way around. If we ignore them they sound as if they are talking sense.